No Vacancy

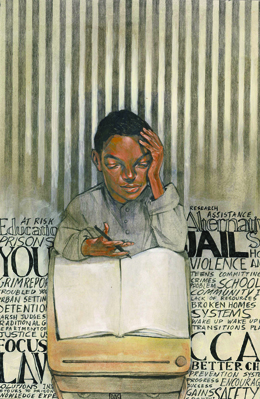

Troubled youth flood Syracuse's juvenile prison system.

By Jessica Assimon

At first glance, teenager Janiese Flagg looks like any other high school senior. Flagg, a senior at Syracuse's Nottingham High School, goes to classes, hangs out with friends, and applies to colleges in her spare time. But six years ago, Flagg’s future wasn’t as promising.

Her middle school suspended her after she got in a fight, landing Flagg in alternative school, where suspended students continue taking classes. Cut off from her peers, Flagg said alternative school essentially excommunicated the so-called “delinquents” from the rest of the students and made it easy for them to drop out.

Left to fend for themselves without an education, many fell victim to gangs and drugs. “At the time, my brother had just passed away and it was kind of hard for me and my family,” Flagg said. “The actual reason I got into the fight was because girls were saying things about my brother.”

Flagg never wound up in a correctional facility, but a number of teenagers, faced with the blunt force of the public school system, end up in juvenile detention. Many become repeat offenders, often returning to juvenile prison shortly after they're released.

The Center for Community Alternatives (CCA) in downtown Syracuse helped Flagg rebuild her life. The center offers rehabilitation to teens, providing professional counseling to help them readjust to life outside detention centers. The CCA’s around 50 employees work directly with teens, creating daily schedules and helping them prioritize their lives.

When Flagg returned to public school in 8th grade, she received an adviser from the CCA to help her adjust. Flagg's adviser came to her school and checked to make sure she didn’t have any problems.

The center’s organizers work with the Syracuse City School District to funnel high school students in alternative schools through its rehabilitation program.

Pedro Noguera, a professor in the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development at New York University, said parents can’t rely on prisons or detention systems to change their children's mindsets. Instead, Noguera said the community needs to refocus its efforts on the school system. “The prisons don’t have the resources. A lot of times they don’t have the expertise to solve the problems by themselves,” he said. “You have to focus on what the school is doing and what the community is doing to really meet the needs of the children.”

While some teens commit crimes that warrant prison time, some end up incarcerated because they come from broken homes, said Marsha Weissman, executive director of the CCA. In August, the U.S. Department of Justice released a grim report of four of New York State’s juvenile prisons. The 18-month investigation found that its residents, age 16 and younger, suffered broken bones, concussions, and spiral fractures, among other serious injuries during incarceration.

“A lot of kids in juvenile prisons are there not because of the nature of the crime, but because the judge thinks their family situation is not as good as it could be,” Weissman explained. “And while there may be problems in family situations, I think it’s clear in the research, including the [Department of Justice] report, that these kids are not getting treated any better in facilities.”

The study also reported that officials at city-run juvenile prisons didn’t follow regulations set by the state and federal governments. In November 2006, a 15-year-old boy died when two staff members pinned him down at the Tryon Residential Center in Johnstown, NY. The Department of Justice continues to investigate the incident, as well as other alleged crimes and civil rights violations by prison guards.

Weissman added that most of those cases involve poor black teens. “If I, as a middle class white person, had a child with a mental health problem, you can be sure that the kid would not get the [same] treatment in the juvenile justice system,” she said.

But sending criminal teens to prison to help them avoid their broken homes also isn’t a fiscally sound solution. Under New York State law, minors must receive an education during their incarceration. Weissman estimated the cost of paying teachers and security guards at $150,000 per prisoner each year. She said states could avoid such high costs if the government included mental health systems and more youth development facilities like the CCA.

But sending criminal teens to prison to help them avoid their broken homes also isn’t a fiscally sound solution. Under New York State law, minors must receive an education during their incarceration. Weissman estimated the cost of paying teachers and security guards at $150,000 per prisoner each year. She said states could avoid such high costs if the government included mental health systems and more youth development facilities like the CCA.

The CCA’s main goal for the 200 youth in its programs is to provide education. Experts say educated youth are more likely to stay out of prison. “We have to use education as the detour to prison,” said Noguera, who researches and writes about the relationship between education and the prison system.

Noguera said he believes juveniles can avoid prison if they receive the education they need early on: “All you have to do is look at the profiles of who is there [in juvenile prison] and it’s the kids who failed, the kids who were disconnected, and the signs start early.”

CCA officials offer transportation to get teens to school. The staff members also call kids to wake them up for class. And it’s not that these kids’ parents don’t care, Weissman explained. Their parents may work an early shift and can’t be home in the morning to wake their child up and see them off to school.

The CCA runs a variety of after school programs as a recreational and social outlet. The center asked teens what they were looking for in a music program, and many said they wanted the technology and equipment to produce hip-hop music. So, with funding and rules established by the teens themselves, the CCA bought a sound studio.

The teens didn’t start mixing tracks right away. Weissman and her staff told them that hip-hop music is essentially poetry and that they should study poetry before entering the studio. The center brought in a local poet to work with the kids and a number of teens found a love for the art.

A few years ago, these new found poets entered a county-wide poetry contest. Out of the 16 finalists, four of them were teens in the CCA program. “These are kids who people think have no talent or skills or won’t amount to much,” Weissman said. “If you give them the right support and encouragement, they can really shine.”

Flagg participates in the center’s peer-advising program. The program trains teens to be leaders in HIV and violence prevention — two problems Weissman said take devastating tolls on troubled youth. Flagg draws on her own life experiences to teach her peers ways to counteract crime and brutality. “I had been there in that situation as a kid, and it was nice to talk to others about it,” she said.

Despite programs led by youth like Flagg, the CCA encounters a number of obstacles trying to integrate youth offenders back into society. Teens returning from prison have a more difficult time getting onto the right path, Weissman said, since their time spent serving a sentence eroded their social and self-management skills. Many can’t rebuild those skills, and wind up back in prison.

Weissman said the stigma of being institutionalized follows youth and, depending how long they’ve been in prison, affects their reentry process: “We want to lock them away and just assume they’re better off away than out in the community, and that’s not true.”

When Weissman had the opportunity to take teens to Geneva, Switzerland to speak before a U.N. Committee, she said people expected her to take honors students. Instead, she took teens from the center. “People were dumbfounded, as if, ‘How could they do this?’” Weissman said. Weissman chose Flagg and three other teens to bring to Geneva in February 2008. And although officials once deemed those teens “at risk,” they were the most qualified to address the issue called “the school to prison pipeline” — one they’ve experienced firsthand.

Upon learning Weissman chose her to travel to Switzerland, Flagg was overcome with shock and excitement because, she explained, the CCA was working on eliminating alternative schools. Though Flagg didn’t speak at the event, she observed and talked with adults after the conference.

This year the Syracuse City School District dropped its alternative schools program, stripping students of that suspension safety net and motivating them to stay in school.

Without the CCA’s support, Flagg might not be where she is today: an international traveler applying to four-year colleges, with hopes of becoming a nurse practitioner. “I think I came a long way and made a lot of progress,” Flagg said. “They helped me make better choices. I’ve done things I’d never thought I’d do.”